Between 2016-2020, the prevalence of gestational diabetes (GDM) rose an alarming 30%.1 As GDM becomes more common, obstetricians need to know when to screen to optimize prenatal care by ensuring timely intervention.

Testing for GDM is generally recommended between 24-28 weeks of pregnancy. However, some wonder if we’d improve maternal and fetal outcomes if we caught GDM even earlier. Today’s focus is on the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology (ACOG) recommendations2 for early screening for diabetes in pregnancy.

What is the basis for early screening?

First, let’s define early screening. GDM screening is typically done between 24-28 weeks. Early screening is any diagnostic screening completed before 24 weeks.

Performing the screening for GDM earlier in the pregnancy could potentially identify women with signs of glucose intolerance. Early interventions in these higher-risk populations can improve outcomes for the baby, like reducing macrosomia and adiposity.3

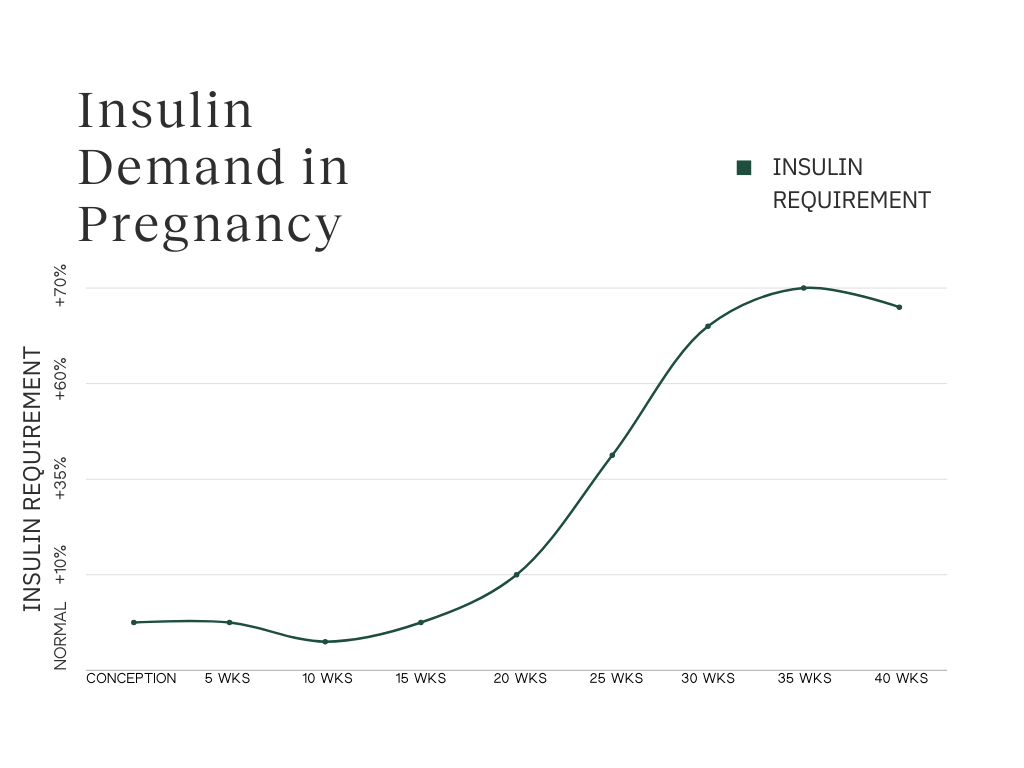

Typically, it’s thought that the stage of pregnancy at which you detect altered blood glucose levels determines the type of diabetes. The developing placenta is producing hormones that interfere with insulin sensitivity and action, so the pancreas ramps up production to compensate.

The insulin demand starts to increase between 15-20 weeks of gestation.

If you have a patient with elevated glucose in the first trimester, it is likely overt or pregestational diabetes, not GDM.

However, there is a subset of individuals who have blood sugars that are elevated, but not quite to the level indicative of diabetes. This has been deemed early GDM.

What does the research say about early gestational diabetes?

Given the impact of uncontrolled diabetes on pregnancy outcomes, detecting glucose intolerance can be valuable to allow for earlier treatment and behavioral interventions. That said, early diabetes screening isn’t yet a standard recommendation for all.

The reason is likely related to the lack of robust research involving early GDM that proves the benefits of early detection.

One of the largest studies of early GDM is the Treatment of Booking Gestational diabetes Mellitus (TOBOGM) trial. This multicenter, randomized controlled trial was conducted to determine whether early detection and treatment of GDM offers any benefit.

A secondary analysis of the data from this trial found that those who were diagnosed early in pregnancy but were not treated until 24-28 weeks had more adverse outcomes, such as preterm delivery, higher birth weight, birth trauma, neonatal respiratory distress, the need for phototherapy, stillbirth, and shoulder dystocia.4

Timely interventions may be key to reducing the negative outcomes in those with early alterations in glucose metabolism. In a 2023 clinical trial published in the New England Journal of Medicine, women who were diagnosed between 4 and 20 weeks and were treated immediately had a modestly lower degree of adverse neonatal outcomes.5

However, some research has shown that interventions like insulin or metformin in early pregnancy may not improve maternal or neonatal outcomes for those with early gestational diabetes.6

Researchers and clinicians agree that current guidelines for routine first-trimester screening need further investigation. A major ongoing observational study, GO MOMs (Glycemic Observation and Metabolic Outcomes in Mothers and Offspring), aims to establish criteria for early pregnancy testing. Meanwhile, early screening is currently recommended for individuals at higher risk of diabetes.

Who should be screened early?

Early screening for diabetes isn’t a blanket recommendation for all pregnancies. If your patient is overweight or obese (BMI ≥25 kg/m², or ≥23 kg/m² in Asian Americans) and has one or more of the following risk factors, it may be appropriate to screen for pregestational diabetes:

- Family history of diabetes (first-degree relative)

- History of heart disease

- Black, Hispanic, Native American, Asian American, and Pacific Islander individuals

- Polycystic ovary syndrome

- Prediabetes (A1c ≥5.7%, impaired fasting glucose, or impaired glucose tolerance)

- Hypertension (blood pressure ≥140/90 mmHg or on medication for hypertension)

- HIV

- Previous gestational diabetes diagnosis

- Aged 35 years and older

- Sedentary lifestyle

What is the best way to screen?

At this time, ACOG recommends a two-step approach to screen for diabetes in pregnancy. First, a preliminary one-hour, 50-gram oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) is performed non-fasting. If necessary, a fasting, three-hour, 100-gram OGTT is done using the Carpenter and Coustan criteria for diagnosis, as seen below:

Since early screening is to detect pregestational diabetes, standard diagnostic criteria for the non-pregnant population could also apply. An A1c ≥6.5%, fasting plasma glucose ≥126 mg/dL, or random plasma glucose levels ≥200 mg/dL with hyperglycemic symptoms (excessive thirst, urination, unexplained weight loss, etc.) may indicate pre-existing diabetes. It should be noted that these tests haven’t been formally validated in pregnancy.

Bottom Line

While early screening is currently reserved for identifying pregestational diabetes in patients with known risk factors, new research is underway to evaluate how early changes in glucose may help identify gestational diabetes sooner. At this time, more evidence is needed before ACOG updates its guidelines to support routine screening for all pregnancies before 24 weeks.

FAQ

1. When a patient is negative for diabetes in their early screening, do you have to repeat the test at 24-28 weeks?

Yes, because of the increasing insulin demand and potential for insulin resistance as the pregnancy progresses, re-screening is recommended.

2. Can a continuous glucose monitor (CGM) be used to test blood sugars instead of the OGTT?

The OGTT is contraindicated in some patients, such as those post-bariatric surgery7, which necessitates an alternative. While you can certainly determine glucose patterns with continuous glucose monitoring (and it may be more acceptable to patients)8, CGMs are not yet recommended by ACOG for diagnosing diabetes in pregnancy. This is also an area of active research.

3. When is it too late to screen for GDM?

Although it’s never too late to detect issues in glucose metabolism—even late pregnancy9—time is of the essence. The lapse between diagnosis and self-management education and monitoring can be a barrier to adequate care for GDM. Fortunately, digital health tools like LilyLink can expedite treatment and increase access to immediate diabetes care.

Whatever method you use for screening, timely care is critical to improving outcomes. LilyLink is a gestational diabetes management platform that helps get patients onboarded and tracking glucose immediately after diagnosis. Learn more or schedule a demo.

References:

- Gregory, Elizabeth C.W. and Ely, Danielle M. "Trends and Characteristics in Gestational Diabetes : United States, 2016–2020" vol. 71, no. 3, 2022. https://dx.doi.org/10.15620/cdc:118018

- Gandhi M, Kaimal AJ, Turrentine M, Caughey AB, Shields A. Screening for gestational and pregestational diabetes in pregnancy and postpartum. Obstet Gynecol. 2024;144(1):e20–e23. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000005612

- Calancie L, Brown MO, Choi WA, et al. Systematic review of interventions in early pregnancy among pregnant individuals at risk for hyperglycemia. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM. 2025;7(3):101606. doi:10.1016/j.ajogmf.2025.101606

- Simmons D, Immanuel J, Hague WM, et al. Perinatal Outcomes in Early and Late Gestational Diabetes Mellitus After Treatment From 24-28 Weeks' Gestation: A TOBOGM Secondary Analysis. Diabetes Care. 2024;47(12):2093-2101. doi:10.2337/dc23-1667

- Simmons D, Immanuel J, Hague WM, et al. Treatment of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus Diagnosed Early in Pregnancy. N Engl J Med. 2023;388(23):2132-2144. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2214956

- Boggess KA, Valint A, Refuerzo JS, et al. Metformin Plus Insulin for Preexisting Diabetes or Gestational Diabetes in Early Pregnancy: The MOMPOD Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2023;330(22):2182-2190. doi:10.1001/jama.2023.22949

- Rodrigues-Martins D, Nunes I, Monteiro MP. The Challenges of Diagnosing Gestational Diabetes after Bariatric Surgery: Where Do We Stand?. Obes Facts. 2025;18(2):187-192. doi:10.1159/000541623

- Di Filippo D, Henry A, Bell C, et al. A new continuous glucose monitor for the diagnosis of gestational diabetes mellitus: a pilot study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2023;23(1):186. Published 2023 Mar 18. doi:10.1186/s12884-023-05496-7

- Cauldwell M, Chmielewska B, Kaur K, et al. Screening for late-onset gestational diabetes: Are there any clinical benefits?. BJOG. 2022;129(13):2176-2183. doi:10.1111/1471-0528.17154